28 October 2020

7 min read

#Corporate & Commercial Law, #Dispute Resolution & Litigation

Published by:

What a crazy year it has been! One trend in the business world that has become more evident to us is a sharp rise in shareholder disputes. These disputes have involved issues such as concerns over access to information, dissatisfaction with decisions at the board and management levels of the business and frustrations with certain actions of business partners (including dealings with shares in the company and company assets). Of course, the easiest and cheapest way to resolve these disputes is for the business partners to talk it through with one another and work out a path forward. However, often the people involved are so adamant that their perspective is right and that of their business partner(s) is wrong, therefore, a negotiated outcome proves very difficult to achieve.

It is usually when the discussions between the business partners have failed that the phone rings and the client explains to us that they want to know how to force their business partner to leave the business and sell their shares, or how to force their business partner to buy their shares in the business so our client can move on with their life.

At this point, all too often, there is an awkward silence when we ask whether the shareholders agreement or the constitution of the company provides for a right to compel the sale or purchase of shares simply because the business partners have had a falling out. The silence is commonly the result of the fact that there is no shareholders agreement, or – if there is a shareholders agreement – neither it nor the constitution gives the parties the right to force an exit from the company on acceptable terms.

The importance of smart structuring and decent contracts

Ideally, the investor should seek to have a majority ownership stake in the legal entity and to be able to control the decision-making at the board and management level of the business. That said, it is not uncommon for business people to take a 50:50 stake in a business entity with another partner, or to take a minority ownership stake, frequently alongside other business partners or investors. This means, among other things, that they may not have control of the board of directors of the entity. Sometimes there are strategic, commercial and financial reasons for opting for a 50:50 or even a minority stake. Whatever the reason, the shareholder should ensure that they protect their interests as well as possible from the outset.

Prevention is better than cure

Prevention is usually more effective and certainly cheaper than a cure. Shareholders would do well to seek professional advice on how they can, for instance, buttress the protection of 50:50 owners or minority parties and how they can best structure their investment. If investors do invest in a legal entity (and especially where they do so as 50:50 or minority investors), they would be prudent to do the simple things well, such as:

To the extent possible, if investors become minority shareholders in an Australian legal entity, they would also be wise to:

Be prepared for the fight

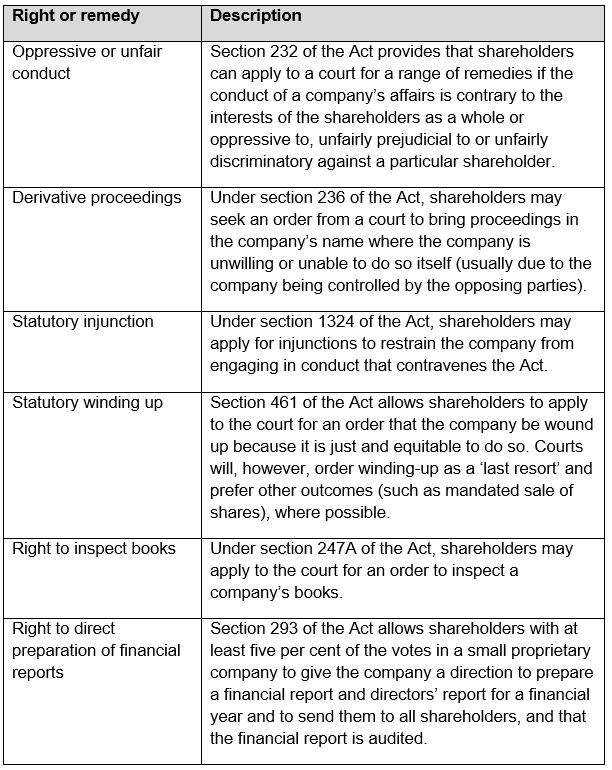

If it becomes clear that there is no way forward for the parties to remain in business and they need to go their separate ways, then having a good quality shareholders agreement and constitution will help. It would also be helpful if the shareholder understands their legal position under Australian law. The law provides mechanisms for upholding the rights and interests of shareholders (and minority shareholders in particular). For instance, the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Act) provides the following, among others, statutory protections of shareholders’ rights:

Knowing how and when these rights can be applied to obtain leverage in respect of negotiated or court-ordered outcomes is crucial for all business owners of private companies.

Parties can use independent facilitators before getting into the deal to help work out what the shareholders arrangements might be. When shareholder disputes arise, it is often best to get legal help sooner rather than later, even during the “negotiation phase” of the dispute resolution process. It often makes sense to involve independent expert mediators to help resolve the more bitter and entrenched shareholder disputes.

Parties should also be aware that they would be best placed speaking with their lawyers before appointing independent expert valuers to value the parties’ shares in the legal entity. This is especially the case where the independent expert valuer’s valuation decision is binding on the parties.

Whilst it is unfortunate for many business owners that these trying times will likely see a further spike in shareholder disputes, having an understanding of the basic legal concepts discussed above can assist business owners to avoid any such disputes spiralling out of control into emotionally and financially destructive legal fights.

For a more in-depth discussion on shareholder disputes, click here to register and watch our presentation which covers how to best approach resolution of shareholders disputes using alternative dispute resolution and/or litigation, key issues to be aware of when acting as a minority shareholder and the protections available for these shareholders.

If you need any assistance on avoiding or resolving a shareholder dispute, please contact us.

Authors: Carl Hinze & Toby Boys

Disclaimer

The information in this publication is of a general nature and is not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Although we endeavour to provide accurate and timely information, we do not guarantee that the information in this newsletter is accurate at the date it is received or that it will continue to be accurate in the future.

Published by: