31 March 2021

8 min read

#Government, #Dispute Resolution & Litigation

Published by:

In claims for public interest immunity, courts have expressed the view that “public interest immunity will not be lightly conferred and it should not be lightly claimed”. It is therefore important, given the close scrutiny of such claims by courts, that government lawyers are aware of the tips and traps associated with claiming public interest immunity. This is particularly so in light of the recent Federal Court decision in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v NSW Ports Operations Hold Co Pty Ltd (No 3) [2020] FCA 1766 (ACCC v NSW Ports) where claims of public interest immunity were considered in detail.

Public interest immunity – first principles

The heart of the common law doctrine of public interest immunity is that the Court will not compel disclosure where to do so would be injurious to the public interest.

The key decision is Sankey v Whitlam,1 where the High Court discussed the two potentially conflicting sides of the “public interest”:

Courts will need to consider, and ultimately balance, these competing public interests against one another in determining whether a claim for public interest immunity ought to be upheld (commonly referred to in judgments as the “balancing exercise”).

The Courts have, in assessing claims of public interest immunity, accepted a distinction between “content claims” and “class claims”:

Typically, class claims are raised in respect of Cabinet documents. The conventional rationale for protecting Cabinet documents from disclosure is to ensure that communications between Ministers at Cabinet meetings may be frank and candid and that decision-making and policy development is uninhibited.

It is, however, the duty of the Court “and not the privilege of the executive government” to decide whether or not particular government documents ought to be disclosed.

While in class claims relating to Cabinet documents, the Court will “lean initially against ordering disclosure”, immunity from disclosure is not absolute. Rather, the classification of the document as being a Cabinet document is a relevant factor that goes to weight in the balancing exercise.

The recent case of ACCC v NSW Ports serves as an important reminder that there is no automatic right to public interest immunity even though documents may, broadly speaking, be considered Cabinet documents.

Guidance from ACCC v NSW Ports

Background

The substantive proceeding arose out of the State of NSW (State) privatisation of three ports – Port Botany, Port Kembla and the Port of Newcastle and allegations made by the ACCC that certain agreements between the State and the commercial parties to these privatisations had the likely anti-competitive effect of deterring the development of a container terminal at the Port of Newcastle.

The ACCC did not commence proceedings against the State. However, the State was subsequently joined to the proceedings by one of the commercial parties filing a cross-claim against the State.

The claim for public interest immunity

The claim for public interest immunity arose due to the ACCC serving a notice to produce on Morgan Stanley (a company that provided advice to the State). The ACCC alleged that documents between Morgan Stanley and the State contained advice as to how the successful bidder for Port Botany and Port Kembla could be protected from competition, which would be material evidence in the substantive proceeding.

The Secretary, Department of Premier and Cabinet for NSW (Secretary) claimed public interest immunity, the basis of which was that the documents fell within a class of documents (i.e. a “class claim”), being Cabinet documents, and that disclosure would prejudice the proper functioning of the government.

Importantly, during the proceeding, the Secretary conceded that the subject matter of the documents was no longer current or controversial.

The main subject matter of the Cabinet documents was the privatisation of the Port Botany, Port Kembla and Port of Newcastle which had occurred in the case of Port Botany and Port Kembla in 2012 and in the case of the Port of Newcastle from 2013 to 2014.

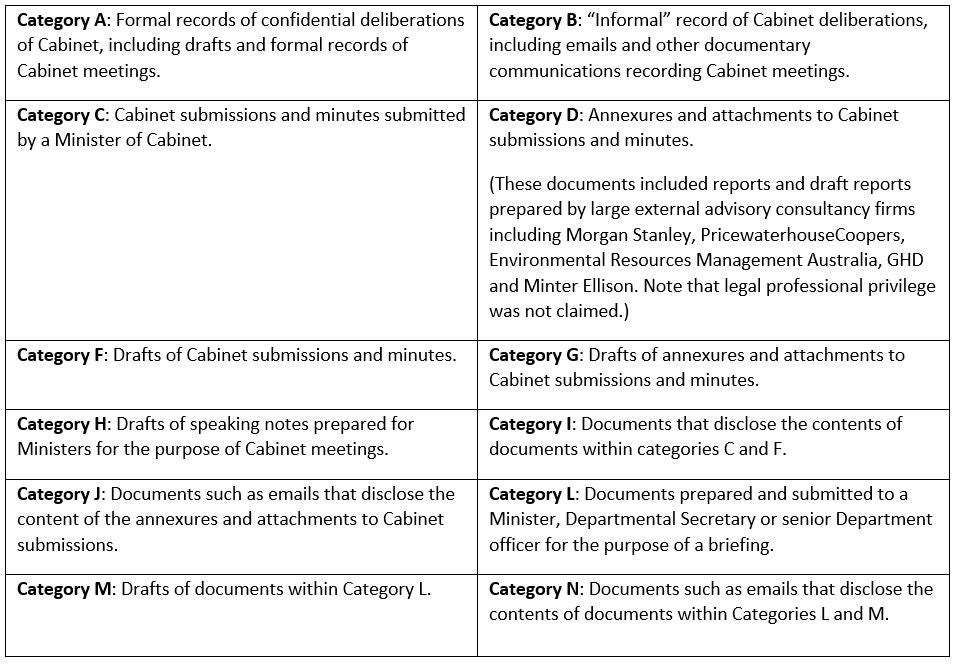

The documents that were subject to the claim for public interest immunity were classified under 12 broad categories:2

The Decision

The Court ordered the production of a number of documents, largely falling within Categories D (annexures and attachments to Cabinet submissions and minutes) and G (drafts of annexures and attachments to Cabinet submissions and minutes), as it was held that the public interest tipped in favour of disclosure, even though, broadly speaking, those documents where considered Cabinet documents. Justice Wigney concluded:

“The case for disclosure is perhaps clearest in the case of the reports and draft reports of external consultants and advisers (Categories D and G), particularly given that the content and subject matter of those reports was mainly commercial, contractual or technical and is no longer current or controversial. Those reports and draft reports also contain some potentially material evidence”

“The remaining documents which are the subject of the Secretary’s claim are immune from production. That is most clearly the case in relation to the documents which disclose or tend to disclose Cabinet decisions or deliberations, or the content of submissions to Cabinet (Categories A, B and C), particularly in circumstances where those documents did not contain any apparently material or important evidence.”

Key takeaways

Immunity is not absolute

The definition of “Cabinet documents” is broad. The decision in ACCC v NSW Ports highlights that different categories of Cabinet documents will enjoy different levels of protection. As such, analysis is needed for every document which is claimed to be immune from disclosure having regard to the type of Cabinet document it is, and the content of the document. As noted by Justice Wigney:

Be aware of reports and advice obtained from external consultants

It is not unusual for government departments involved in a proposed transaction or policy initiative that requires Cabinet approval, to engage external consultants to assist it to brief its Minister and make submissions to Cabinet. It is also not unusual that advice, papers and reports prepared by these consultants for these purposes are incorporated into submissions to Cabinet in some form.

Whether such documents will attract public interest immunity is not clear cut. It is important, to be aware, as demonstrated in the ACCC v NSW Ports case, that simply attaching a label of “Cabinet-in-Confidence” to a document from an external consultant without being able to demonstrate that the document:

will weigh heavily against upholding a claim for public interest immunity in such documents.

The Court in ACCC v NSW Ports, also, did not accept the Secretary’s submission that the disclosure of the reports of external consultants would result in Cabinet being more reluctant to seek such advice in the future. Justice Wigney said that it was “highly dubious, if not somewhat fanciful” that sophisticated external advisors or consultants would alter or temper advice if they were to be assured that advice would never be disclosed.

Be aware of how evidence is presented

It is also important when you are making claims of public interest immunity that detailed evidence is provided to the Court so that the Court can make an appropriate assessment of the public interest immunity claim.

Justice Wigney in ACCC v NSW Ports noted “general deficiencies” in the Secretary’s evidence provided to the Court. The following tips and traps arising out of the decision of Justice Wigney may assist you if you are required to make a claim for public interest immunity in Court:

Should you have any queries regarding public interest immunity claims or privilege claims more generally, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Authors: Joanne Jary & Sasha de Muelenaere

[1] Sankey v Whitlam (1978) 142 CLR 1.

[2] Note that there was no “Category E”.

Disclaimer

The information in this publication is of a general nature and is not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Although we endeavour to provide accurate and timely information, we do not guarantee that the information in this article is accurate at the date it is received or that it will continue to be accurate in the future.

Published by: