01 July 2020

20 min read

#Planning, Environment & Sustainability, #Construction, Infrastructure & Projects, #Property & Development

Published by:

On 11 June 2020, the Design and Building Practitioners Act 2020 (NSW) (Act) took effect.

The new Act is about restoring public confidence in the NSW building industry by regulating the activities of those who design and construct new buildings.

The aim is to ensure that all the key participants are regulated and that the designs for buildings comply with the Building Code of Australia (BCA) and that any building work done complies with those designs.

The Act comes as part of the NSW Government’s response to the Shergold Weir Report which focused on the shortcomings in the implementation of the National Construction Code following concerns raised at the national level about building defects and combustible cladding.

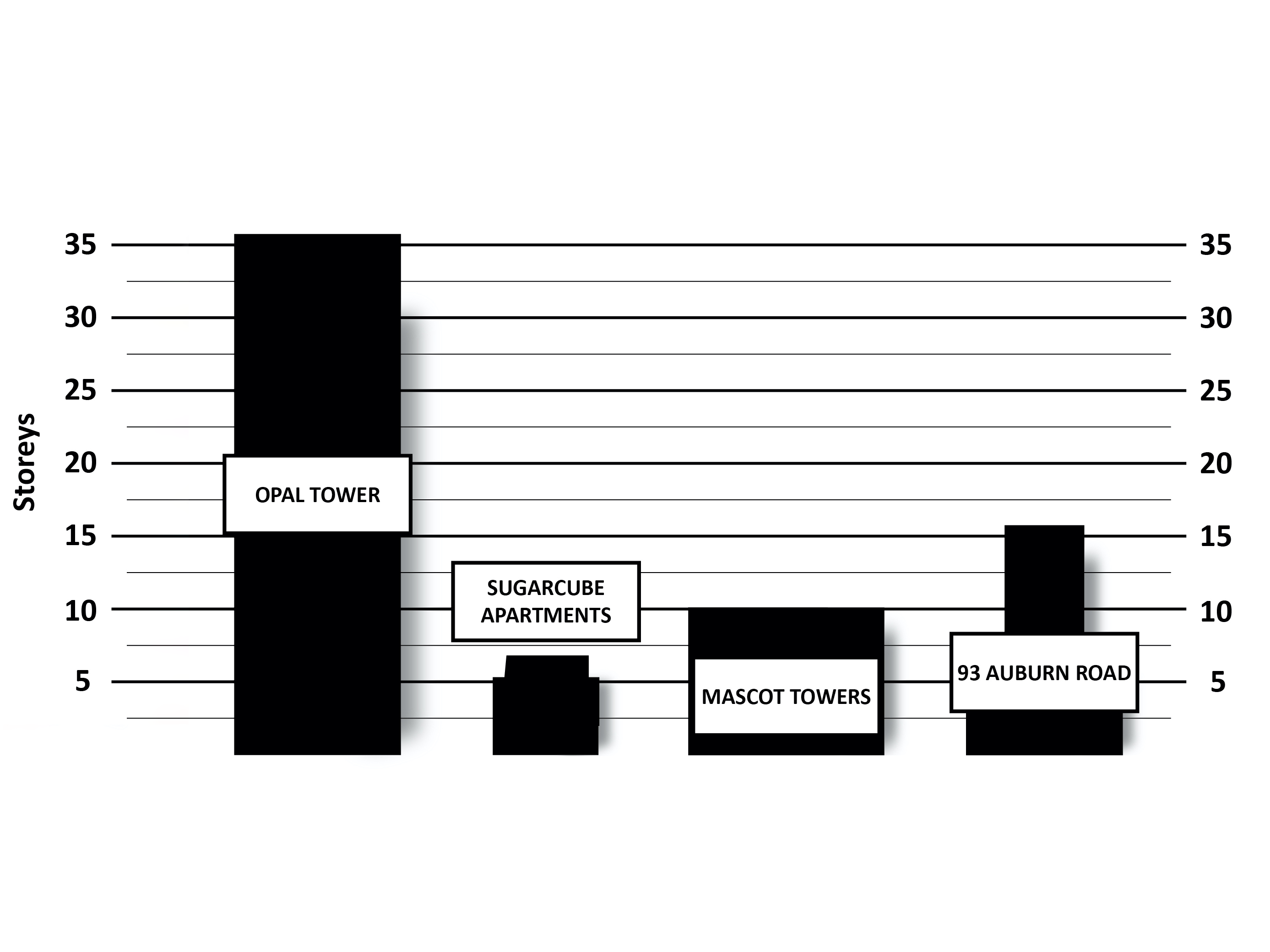

Defects in certain new high-rise apartment buildings have been well publicised. Whilst the Act seeks to address these problems, questions remain about whether the Government’s adopted approach represents best practice regulation.

An examination of building defects in residential multi-owned properties by researchers from both Deakin and Griffith Universities makes for sobering reading:[1]

Allied to the problem of poor quality construction are the problems caused by the dominant business models that leave very little in the way of recourse for new owners.

Many new apartment buildings are built by developers using special purpose vehicles, which are dissolved once the units are sold. Off-the-plan purchasers contract with the developer and do not have a direct contractual relationship with the builder. The High Court has established that there is no duty of care between the builder and an owners corporation for pure economic loss resulting from defects. Although owners have the benefit of statutory warranties from the builder (and the developer), these are enforceable for six years for major defects and two years for defects other than major defects. In those circumstances, the cost of defect rectification frequently falls on the owners.

If these are the problems. What then are the solutions?

The Government has identified the Six Reform Pillars. Building a better regulatory framework to transform the focus of the regulator is amongst one of those pillars.

The Act contains a number of key changes to be aware of, namely:

The Act is only partially in force with the new statutory duty of care effective from 11 June 2020, and the regulation of design and building work, practitioner registration, disciplinary actions, investigations and enforcement provisions coming into effect on 1 July 2021.

The term “building work” is defined in s 4 of the Act (other than for the purpose of the new duty of care) as work involved in, or the coordinating or supervising of work involved in, one or more of the following:

To this extent, the fact that the Regulations have not yet been released means that it is difficult to determine how far the scope of “building work” will reach, and which classes or types of buildings will be brought within the scope of the bulk of the Act. The second reading speech suggests classes 1, 2, 3 and 10, but we await the Regulation.

Nevertheless, the fact that the definition extends to include those coordinating or supervising building work, as well as the physical building work itself, means that the intention is for the definition to be far reaching.

For the new duty of care, a building is defined more broadly, by the definition in the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act to include "part of a building, and also includes any structure or part of a structure (including any temporary structure or part of a temporary structure) but does not include a manufactured home, movable dwelling or associated structure...". This appears to give the application of the duty of care a potentially wider application in terms of classes of buildings, to the remainder of the Act, although on an alternative reading it applies currently only to residential building work. This remains to be tested and may well be clarified when the Regulation is released. This has now been clarified in a 2022 decision, see our article here.

Arguably the most significant change arising from the Act is the introduction of a non-delegable and retroactive statutory duty of care.

The imposition of this duty of care is unprecedented and effectively means that from 11 June 2020 anyone who carries out “construction work” will have an automatic duty to exercise reasonable care to avoid economic loss caused by defects or construction work.

The duty of care is owed to each owner of the land in relation to which the construction work is carried out, including owners corporations, as well as to each subsequent owner of the land.

It is noteworthy that the definition of “construction work” is extremely broad and includes:

The scope of “economic loss” for the purpose of this duty is equally broad and includes not only the cost of rectifying defects (including damage caused by defects), but also the reasonable costs of providing alternative accommodation where necessary.

Critically, the duty of care is retroactive, meaning that owners and subsequent owners of land may claim for a breach of statutory duty where:

The retroactive application of the duty provides a remedy for those who may not otherwise have had one. Equally, it exposes sectors of the industry to liability in circumstances where at the relevant time work was being carried out, that liability did not exist.

A person to whom the duty of care is owed is entitled to damages for a breach of the duty, as if it were a duty established by the common law. This means that while a duty of care will be automatically owed, any person who wants to proceed with the litigation will be required to meet the other tests for negligence established under the common law and the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW).

Consistent with the existing position under the common law, the duty of care will be subject to the limitation period that applies to negligence claims under the Limitation Act 1969 (NSW). This means that there will be strict time limits within which to bring a professional negligence claim and that court proceedings need to be commenced within six years from the date on which the loss or damage accrues.[2]

The duty was originally not intended to benefit owners who are developers or large commercial entities, as the legislative considered these entities to be sufficiently sophisticated and able to contractually and financially protect their commercial interests. This has now been clarified in a 2022 decision, see our article here.

The Act provides that the Secretary of the Department of Customer Service (Secretary) is to maintain a register of registered practitioners that contains the information prescribed by the regulations.

The Act defines “registered practitioner” as including:

A registered practitioner can be an individual or a company.

The Act provides that a person is to make an application for registration which is to be determined by the Secretary who may grant or refuse the application. The Secretary may refuse to register a person where, for example, the Secretary is of the opinion that the applicant does not have the appropriate qualifications, skills, knowledge or experience, or where the person “is not a suitable person to carry out the work” subject of the application.

Once granted, a registration remains in force for a period of one, three or five years as may be specified by the Secretary, unless it is cancelled or suspended sooner.

This broad definition of registered practitioner means that many industry players will be caught by the registration regime and will be brought within the scope of the Act. This means that the Secretary will carry a significant administrative burden to develop a registration procedure, process those registration applications, and develop and publish those registrations on an online register that may be freely accessible by the public.

This is nothing short of a mammoth task. Consequently, it is critical that the Secretary is furnished with sufficient resources to ensure that all applications are processed within a reasonable timeframe. Any failure to process registration applications quickly and efficiently will mean that a large number of practitioners will be unable to practice as “registered practitioners” in accordance with the Act.

The Act has introduced compulsory compliance declarations that must be given by designers and builders to ensure compliance with the BCA.

A principal certifier who is responsible for issuing OCs must not determine an application for an OC (and therefore must not issue an OC) unless they are satisfied that all compliance declarations required to be given have been lodged in accordance with the Act.

Three types of compliance declarations have been introduced:

Failure to comply with the requirements for compliance declarations carries a maximum penalty of $165,000, while providing a compliance declaration that a person knows to be false or misleading carries a maximum penalty of $220,000.

The aim here is clearly to hold up the issuing of an OC unless registered practitioners have essentially signed off on the design or building work as complying with the BCA, or carried out works to rectify identified non-compliances.

In this way, the Act is similar to the Residential Apartment Buildings (Compliance and Enforcement Powers) Act 2020 (RAB Act) which also seeks to prevent the issuing of OCs or the registration of a strata plan for residential apartment buildings where certain requirements are not met. For a full discussion of the RAB Act and its implications for the industry, see our article here.

Practitioners providing compliance declarations must be adequately insured. For the most part, the Act relies on the regulations to prescribe the requirements relating to adequate insurance. This means that until these regulations are published, the scope of the requirement for insurance is not known.

However, even at this stage, it is clear that these requirements for insurance may provide issues in the context of the duty of care which has retrospective operation. This means that insurers will now need to take into account any work the practitioner has completed in the last 10 years to appreciate the scope of their liability.

Unsurprisingly, the requirements for registration of practitioners bring with it new disciplinary oversight of these participants. In particular, s 64 of the Act provides grounds on which the Secretary may take disciplinary action against a registered practitioner, and includes (but is not limited to) the following grounds:

If the Secretary forms an opinion that there may be grounds for taking disciplinary action against a practitioner, the Secretary may give notice inviting the practitioner to show cause why disciplinary action should not be taken. The requirement to provide a show cause notice is not a mandatory pre-condition to the exercise of disciplinary action and the Secretary may take immediate action where to do so is in the public interest.

Generally, the provision of a show cause notice is considered an important check and balance on enforcement powers because it entitles a person to put forward their case and make submissions in their defence. We would therefore hope to see the Secretary adopt a policy in favour of issuing show cause notices as a matter of course, despite the fact that it is entitled to proceed to take disciplinary action without notice. Failure to do so would, in our view, be contrary to a minimum standard of procedural fairness owed to practitioners who might, as a result of that disciplinary action, be prevented from practising in their profession following a suspension or cancellation of their registration.

We take this view because the scope of the powers afforded to the Secretary in relation to taking disciplinary action are significant. For example, if the Secretary is satisfied that a ground for disciplinary action against a practitioner has been established, the Secretary may (among other things):

A person aggrieved by a decision of the Secretary to take disciplinary action may make an application to the NSW Civil and Administrative Tribunal for administrative review of that decision.

The Act also introduces broad investigative powers which enable “authorised officers” appointed by the Secretary to:

As is the usual course, these investigation powers are accompanied by an offence that a person must not obstruct, hinder or interfere with an authorised officer in the exercise of their functions.

These information gathering provisions replicate those provided for under the RAB Act and are far-reaching, although not unusual in legislation of this kind.

The Act also gives the Secretary the power to issue a stop work order if the Secretary is of the opinion that the work is or is likely to be in contravention of the Act, and the contravention could result in significant harm or loss to the public or occupiers or potential occupiers of the building to which the work relates.

However, unlike in the RAB Act, a stop work order issued under the Act only lasts for a maximum period of 12 months from the date on which the order takes effect.

Breach of a stop work order carries a maximum penalty of up to $330,000, and up to $33,000 per day in the case of a continuing offence for body corporates and $110,000 and up to $11,000 each day for individuals.

An appeal against a stop work order may be commenced in the Land and Environment Court, but only if the appeal is brought within 30 days of service of the notice. It is also noteworthy that an appeal does not stay the order, meaning that the order must be complied with while the proceedings are on foot.

Given the severe consequences of the making of a stop work order, 30 days is not a long window and it means that urgent legal advice will need to be sought the moment that a stop work order is issued. This short appeal timeframe also has the consequence that appeals will need to be lodged against an order to preserve the appeal right while a developer undertakes their own investigations in respect of the alleged breach. This is not only highly inefficient, but may also unnecessarily burden the Court.

The NSW Government now has the power to regulate almost everyone involved in the design and construction of new buildings, but if the Act is to solve the problems which have been identified, there are a couple of important points the Government would be well advised to consider in the preparation of the necessary regulations and any accreditation scheme.

Perhaps if those points were taken into account we could be confident not just about restoring confidence in the market for new apartments but also about reducing the number of defects that occur.

The effectiveness of this reform initiative needs to be measured by its effectiveness in reducing defects, not by any other measure.

Author: Christine Jones

[1] An Examination of Building Defects in Residential Multi-owned Properties, https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0030/831279/Examining-Building-Defects-Research-Report.pdf

[2] Second Reading Speech by Mr Damien Tudehope (Minister for Finance and Small Business) dated 2 June 2020, Legislative Council Hansard, 2 June 2020, page 67.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Design and Building Practitioners Act 2020 (NSW) s 3.

[5] Ibid s 8.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid s 17.

Disclaimer

The information in this publication is of a general nature and is not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Although we endeavour to provide accurate and timely information, we do not guarantee that the information in this newsletter is accurate at the date it is received or that it will continue to be accurate in the future.

Published by: