12 April 2023

8 min read

Published by:

Our previous instalment in this series provided a refresher on the changes in Australia’s work health and safety landscape, including an overview of the codes of practice for managing psychosocial hazards adopted in different states.

In this next part, we look at the new Queensland code and walk through some practical considerations for businesses. We begin by revisiting key concepts regarding an employer’s duty to ensure their employee’s health and safety at work.

Under the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (Qld), businesses are described as “persons conducting a business or undertaking” (the abbreviations of PCBU and WHS Act will be used for the remainder of the article). The key part of that is “business or undertaking”. Your organisation can only, and should only, concentrate on its obligations as they relate to work that is within the limits of your business.

There are also specific duties for officers under the WHS Act. Section 27 of the WHS Act sets out that if a PCBU has a duty or obligation under the WHS Act, an officer of the PCBU must exercise due diligence to ensure that the PCBU complies with that duty or undertaking. Subsection (5) provides the meaning of due diligence, which includes, for example only, taking reasonable steps to acquire and keep up-to-date knowledge of work health and safety matters.

The meaning of ‘officer’ under the WHS Act has the same meaning as ‘officer’ within section 9 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), which includes, amongst others:

Based on the above, there is a strong argument that employees from the top of the organisation down to middle management are captured by the definition of ‘officer’. In circumstances where we have seen a significant focus on prosecuting officers for breach of their duties, it is critically important to give officers of your business enough time to ensure they comply with their duties.

It is also equally important to differentiate when employees, like managers, are acting in their capacity as an officer or in their day-to-day duties. Understanding, and being able to identify, this distinction is crucial especially if a prosecution is commenced against an officer following a serious workplace accident.

How does this relate to psychosocial hazards? A quick read of the common psychosocial hazards listed in the code of practice shows the potential for such hazards to cause serious psychological injuries. Unfortunately, there have been recent examples of workplace incidents resulting in the death of workers as a result of the listed psychosocial hazards in the code of practice. While it is a whole new topic for us to consider whether a PCBU’s conduct caused the death of those workers, it is now a requirement for PCBUs to manage psychosocial hazards so it is something that is arguably on the table.

Consultation

The first step in complying with the code of practice is to ensure that you have consulted and discussed any workplace changes and risks with your workforce who are or are likely to be affected by a psychosocial hazard. If you have already had this conversation, check what consultation procedure was agreed to and follow that procedure. If you do not have an existing consultation agreement in place, you will need to consult with your workforce and develop an agreed procedure.

Identifying the hazards

When consulting your workforce about psychosocial hazards (through the agreed consultation procedure), you will inevitably obtain feedback – this is a good starting point for identifying the psychosocial hazards. However, it is not enough to solely rely on that feedback. You should also consider the following:

If your business operates in multiple locations or you have multiple specific teams of people within your business, it is unlikely that you can take a holistic/big picture approach to identifying risks. Instead, you will need to focus on tasks or location-specific assessments and tailor them accordingly. Also remember that you must identify reasonably foreseeable hazards, including future hazards that may not be apparent in the workplace. For example, after a traumatic workplace event, there may be significant psychosocial and psychological hazards associated with witnessing the incident and being required to provide a statement shortly after the event.

Assessing the risks

A risk assessment is a critical tool in documenting and assessing identifiable risks in your workplace. Similar to the considerations noted above, it may not be sufficient to do one risk assessment to cover the entirety of your business. If there are multiple ‘work groups’ within your organisation, you will need to undertake a risk assessment of the hazards and risks relevant to that work group. This is particularly important where, for example, one work group may be exposed to work-related violence and aggression as these are very specific risks. For such specific risks, it is appropriate to conduct a standalone risk assessment.

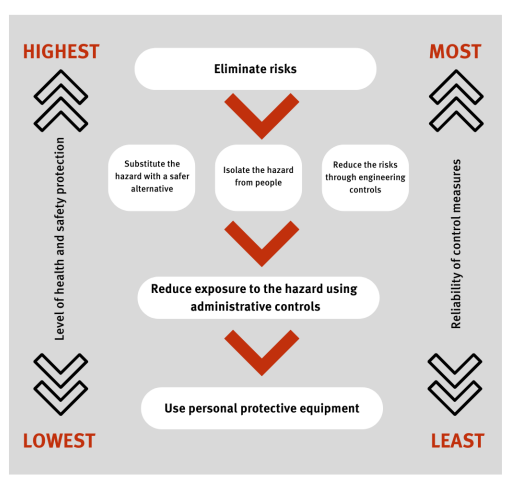

The code of practice provides a detailed guide for conducting a risk assessment. As it stands, each business should have already, at some point in time, completed a risk assessment in the course of establishing safe systems of work. Businesses should also consider the hierarchy of controls when conducting their risk assessments and identifying control measures (see below the Hierarchy of Controls diagram from the code of practice for psychosocial hazards).

Control measures

In our view, identifying control measures is the most critical step for businesses in assessing their risks associated with psychosocial hazards in the workplace because your risk assessment will become a live document that contains the specific measures you are committing your business to in order to control any identified risks. Again, why is this important? Because in the event of an incident, this document may be used to determine whether you complied with your duties under the WHS Act. Any failure to meet or action the established control measures will be documented evidence of a failure to meet and execute your duties. It may also be used as a tool to prosecute officers for failing to ensure that the PCBU complied with its duties.

For PCBUs, what are the key factors to consider when identifying control measures? Our top three considerations are:

Let’s look at a practical example.

The code of practice for psychosocial hazards lists “low job control” as a common psychosocial hazard. By definition, this refers to “workers having little or no control over what happens in their work environment, how or when their work is done or the objectives they work towards.” Some examples include unpredictable working hours and little or no involvement or input into decisions that affect workers.

What control measure might be identified for this hazard? A possible measure could be regularly scheduled meetings between the worker and their supervisor to set an agenda to cover a specific period. For example, the worker and their supervisor could meet weekly to discuss the work to be completed in that time, identify and agree on how the work should be completed, identify the objectives and the expected outcome.

However, the practicality of this control measure depends on the size and structure of the business. Where the supervisor has only two workers reporting to them, it may be practical to schedule these meetings. Where the supervisor manages 10 workers, it is unlikely that it is practical or achievable. Therefore, it may be more practical to introduce several control measures to address the hazard, for example:

Refrain from overcomplicating control measures. If your business already engages its workers in weekly team meetings (the control measure in our above example), do not set up further meetings to discuss or address other risks identified in the workplace. Instead, ensure you include that agenda in those weekly meetings.

It is also important not to over-commit on control measures simply because it looks good on paper. When considering physical control measures (i.e. physical changes to the work environment to improve ergonomics), again, ensure that the controls are physically practical and achievable. For example, it is only practical to re-arrange workstations to create an “open-plan/collaborative work environment if it is physically or financially possible.

The key is to remember that the process of identifying hazards and the risk assessment tool, which includes the identified control measures, is crucial ‘live’ evidence of your compliance with the code of practice and your obligations under the WHS Act. Failure to comply could lead to a range of consequences, which we will explore in the final part of this series.

If you have any questions about this article, please get in touch with a member of our national Workplace Relations & Safety team below.

Disclaimer

The information in this article is of a general nature and is not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Although we endeavour to provide accurate and timely information, we do not guarantee that the information in this article is accurate at the date it is received or that it will continue to be accurate in the future.

Published by: