22 June 2022

6 min read

#Transport, Shipping & Logistics, #Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG), #Planning, Environment & Sustainability

Published by:

The time to decarbonise is now. The UN wants all modes of transport (globally) to get to net-zero emissions by 2050. Research shows this target is possible for the Australian sector.

Given our relative distance from our trading partners, but with the advantage of abundant renewable energy sources, Australia needs to find ways to export (and import) goods efficiently. One opportunity we discussed last year is to commercialise carbon-free green ammonia as an alternative bunker fuel for vessels.

The Australian transport industry has four sectors: Maritime, freight and logistics, rail and aviation.

Each year, about four billion tonnes of goods (or 163 tonnes of freight per person) are delivered across Australia. Over 70 per cent of our total trade in goods and services is with our APEC partners (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation). In short, freight systems and supply chains are the backbone of our economy. These operations are made possible by the National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy.

At the same time, domestic and international transport contributes 20 per cent of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions worldwide. Without immediate action, that number could increase to 40 per cent by 2030 and 60 per cent by 2050.

As a result, ESG-conscious investors, regulators, customers and employees are pressuring leaders of transportation and logistics companies to decarbonise assets, go ‘green’ and commit to sustainability targets.

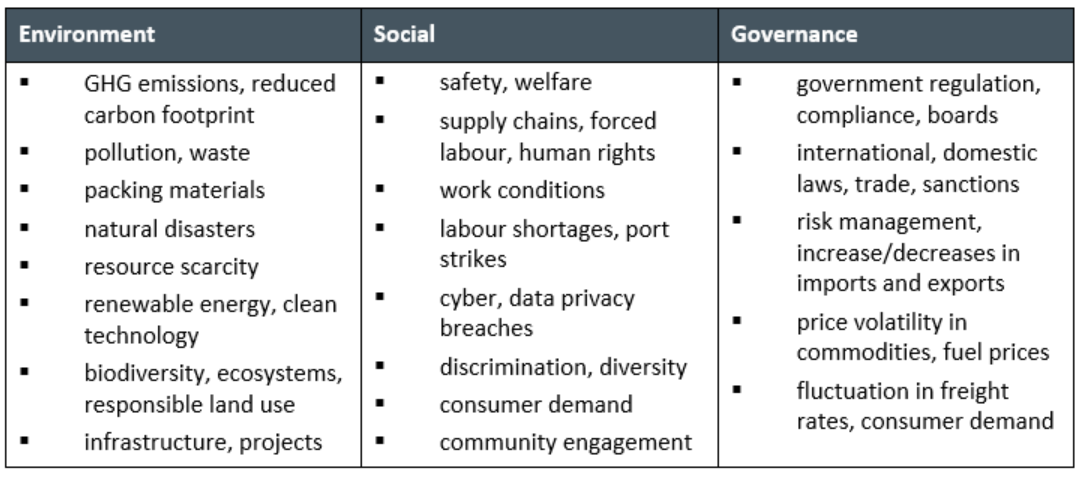

The main ESG industry risks are:

For a more detailed explanation of what ESG is, read our article here.

Next, we look at some topical ESG issues in the transport context.

In 2020, transport accounted for around 18 per cent of Australia’s GHG emissions. These come from the combustion of fossil fuels, mainly petroleum and diesel for transportation.

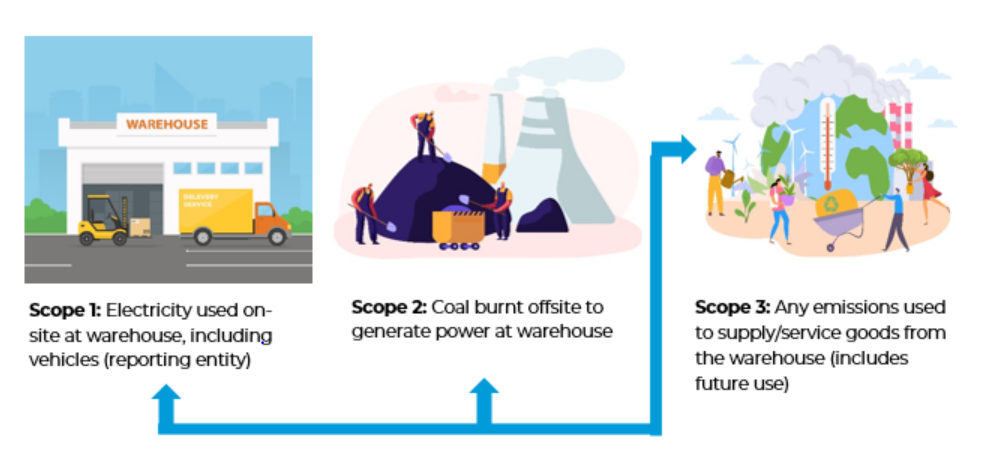

Many large Australian transport operators and logistics companies must report their GHG emissions because of environmental and health concerns. These are categorised by ‘scope’ under the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act 2007 (Cth) and National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Regulations 2008 (Cth) (NGER Scheme):

Scope 3 emissions are not included in the NGER Scheme.[1] These are released indirectly from all upstream and downstream activities in the supply chain from the scope 1 facility onwards. Here’s an example:

In summary, scopes 2 and 3 are caused by scope 1. A company that produces scope 3 emissions are essentially ‘someone else’s’ scope 1 and 2 emissions.

The potential for ‘double counting’ arises if two companies try to claim the same emissions reduction to stay below their calculated baseline and receive ‘Australian Carbon Credit Units’ (ACCUs), which they then surrender to further offset their net emissions.

An important issue for larger operators is accounting for GHG emissions in their supply chains. Why? Emissions are often spread across a complex network of suppliers and released in different locations when labour is outsourced.

Take an example export supply chain:

The factory’s scope 1 and 2 emissions may be relatively low but the bulk of the emissions are scope 3 when the cargo is transported.

Scope 3 are the biggest contributors to climate change and often represent the largest portion of a companies’ emissions inventory. However, because they are not reportable under the NGER Scheme (or included in the nation’s emissions budget) these emissions can’t be quantified. This is when the accounting task becomes trivial.

The factory is responsible for scope 1 and 2 but scope 3 arguably falls outside their direct control or ownership onto the other operators. The questions are then, whose responsibility is it to reduce scope 3? Is the factory justified in not taking responsibility for its share?

From an ESG perspective, the answer is shared and collaborative. For the purpose of supply chains, the point is to assess the overall emissions produced and for each party to realise the extent of their own output. That way, they can set a reduction target to manage their climate impact and attract ESG investors.

Operators should:

If you have any questions or are seeking assistance with developing an ESG strategy or framework for your business, please contact us below or get in touch with our team here.

Authors: Geoff Farnsworth & Isabella Costa

[1] Note, these can be used under the Australian National Greenhouse Accounts (a series of reports and databases published by the Australian Government Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources that estimate Australia’s GHG emissions from 1990 onwards).

Disclaimer

The information in this article is of a general nature and is not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Although we endeavour to provide accurate and timely information, we do not guarantee that the information in this article is accurate at the date it is received or that it will continue to be accurate in the future.

Published by: